Majestic. Deadly. Precise. These raptors command both fear and respect as they soar across skies worldwide. I speak of the Accipitriformes - the diurnal birds of prey that include the mighty eagles and hawks that have captured the human imagination since antiquity.

Bound by razor-sharp talons and piercing hooked beaks, these efficient hunters demonstrate mastery of their airborne domains. Gliding effortlessly upon thermal drafts or diving at heart-stopping velocities to clutch unsuspecting prey, their aerial acrobatics never cease to amaze.

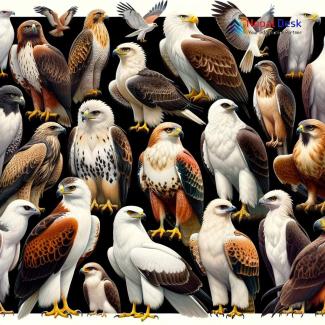

The Accipitriformes display breathtaking diversity - from the tiny, insect-plucking pearl kite to the vast wingspan of the Philippine eagle capable of seizing large mammals and reptiles. Over 250 species are strong globally, they inhabit every continent save Antarctica and thrive in grasslands, forests, deserts, and wetlands alike.

The Accipitriformes trace their origins back over 50 million years to the Eocene epoch. While the earliest known fossils hail from Europe, these consummate fliers eventually dispersed worldwide to occupy an astounding array of ecological niches.

Their continued success in the face of habitat destruction and environmental threats testifies both to their evolutionary resilience and to the success of conservation initiatives established on their behalf.

So next time you admire the grace of an effortless glide or shutter at the sudden explosive force of a raptor’s stoop, remember you are witnessing the culmination of tens of millions of years of aerial refinement. The Accipitriformes' marriage of lethal beauty and consummate skill secures their enduring status as royalty in the skies.

Characteristics of Accipitriformes

Physical Features

Accipitriformes display incredible diversity in size, with wingspans ranging from around 60cm in the pearl kite to over 2 meters in the Philippine eagle. Despite size differences, all raptors share common physical adaptations that aid their roles as predators.

Sharp, curved beaks deliver lethal blows and tear flesh. Powerful talons serve as deadly grappling hooks to clutch and carry prey. Plumage patterns often camouflage raptors within their habitats during hunts. For example, the northern goshawk's slate gray back blends into tree trunks as they perch awaiting prey.

Many Accipitriformes also possess fleshy ceres - bare skin that covers their nostrils - which may help focus scent. Raptors tend to have excellent long-distance vision thanks to large, forward-facing eyes. Their nictitating membranes protect eyes during high-velocity stoops.

Behavioral Traits

Using impressive aerial capabilities, Accipitriformes employ a range of hunting techniques based on preferred prey. Eagles and hawks soar at great heights scanning for mammals, reptiles, and amphibians to snatch with powerful talons. Kites gracefully glide closer to the ground to snare insects and lizards mid-flight with precise movements.

Vultures use soaring flight to scan vast areas for carrion on which they feed. While less agile, their nostrils allow them to detect decaying flesh at impressive distances.

Some large eagle and vulture species take advantage of thermals and updrafts to traverse vast distances during annual migrations between breeding and wintering grounds.

Reproduction and Lifespan

Monogamous pairs create nests called eyries, typically built high up on cliffs, in large trees, or upon flat ground in remote locations for open country species.

Females lay 1-4 lightly colored eggs in early spring that hatch after an incubation period ranging from 30 days to over 2 months depending on species. Young fledge 8 weeks to 6 months later. Juveniles reach breeding maturity from around age 2 (kites) up to age 5 or older (large eagles/vultures).

In the wild, most Accipitriformes survive between 10-25 years, with large eagles occasionally living upwards of 35 years. In captivity, lifespans can extend significantly past 40 years.

Extant families of Accipitriformes order

Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles, Kites, Harriers, Buzzards)

By far the largest family within the order, Accipitridae has representatives on every continent excluding Antarctica. This highly diverse group contains over 220 species displaying remarkable variety in size and hunting techniques. They are united by shared physical traits for capturing and feeding on prey including sharp talons, large hooked beaks, and outstanding vision.

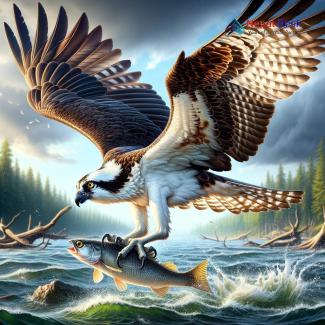

Pandionidae (Ospreys)

These distinctive fish-hunting raptors are found across every continent except Antarctica. There is only a single living species - Pandion haliaetus - known for its striking white and brown plumage. While Pandionidae share traits like Sharp talons and excellent vision with other Accipitriformes, they demonstrate specific adaptations suited for piscivorous diets like reversible outer toes and plumage specially structured to resist water saturation.

Sagittariidae (Secretary Bird)

Another monotypic family, Sagittarius serpentarius has distinctive features separating it from other Accipitriformes. With long featherless legs for striding over the savanna and lanky eyelash-like feathers around its eyes, the secretary bird appears almost stork or crane-like in its proportions. However, the hooked beak and large talons still enable this terrestrial hunter to overpower sizeable snake, lizard, and rodent prey.

Cathartidae (New World Vultures)

Distinct from the Old World vultures of the Accipitridae family, New World vultures occur only in the Americas. With over a dozen species, they demonstrate adaptations for scavenging lifestyles like featherless heads for reaching inside carcasses and a heightened sense of smell to detect decaying meat.

However, they still retain talons and beaks shared by other Accipitriformes. Recent genetic evidence suggests they may be more closely related to storks than birds of prey.

Global Distribution and Habitat

With over 250 extant species, Accipitriformes has achieved a truly global distribution, inhabiting every continent except Antarctica at some point during the year. Only ospreys (Pandionidae) and certain Accipitridae like the peregrine falcon can be found on all continents.

Remarkably, raptors have successfully adapted to exploit a wide range of habitats. Many Accipitridae species inhabit forested areas which provide abundant arboreal or ground-dwelling prey and elevated perches for hunting. Northern goshawks blend into the understory, while harpy eagles rule the rainforest canopy.

Grasslands and deserts host adaptable Buteos like rough-legged buzzards and red-tailed hawks perfectly suited to spotting small mammal prey against sparse vegetative cover. Craggy cliffs and mountains provide nesting sites for golden eagles and Andean condors that survey epic landscapes for signs of movement. Even tundra and icy regions at extreme latitudes support hunting snowy owls and rough-legged buzzards.

Wetland species like ospreys and white-tailed kites employ specialized hunting techniques to take advantage of abundant fish, amphibian, and insect life associated with rivers, marshes, and shorelines.

This impressive flexibility stems from varied sensory capabilities, dietary preferences, and flying prowess. For example, turkey vultures' enhanced olfactory bulb and expansive wings allow them to pinpoint carrion across vast North American ranges. Such adaptability explains why habitat destruction represents the primary threat to most raptors rather than narrow climate tolerances.

Given appropriate food, shelter, and nesting substrate, Accipitriformes stands ready to conquer the skies above nearly any landscape.

Ecological Importance of Accipitriformes

As predators, Accipitriformes play vital regulatory roles within ecosystems. Raptors help control populations of species lower on the food chain which prevent prey numbers from spiraling out of control. Declining raptor numbers can cause surges in organisms like rodents and insects with cascading impacts across trophic levels.

However, Accipitriformes selectively hunt vulnerable individuals like juvenile, injured, or diseased prey. This prevents domination by a single pathogenic strain and enhances overall gene pool diversity.

For example, bald eagles help curb rapidly reproducing fish populations in North American waterways. Golden eagle predation provides natural selection pressure that contributes to faster jackrabbit breeds with enhanced escape abilities.

As apex predators and keystone species, raptor presence frequently correlates directly with ecosystem health due to their sensitivity to bioaccumulation of toxins, habit degradation, and declining food sources. Significant drops in expected raptor numbers within an area may indicate wider issues with pesticide-treated fields destroying rodent populations, acid rain contaminating fish, or logging activity stripping critical nesting trees.

Consequently, conservation initiatives monitor breeding populations and reproductive success of select Accipitriformes like bald eagles and ospreys as barometers for local environmental conditions. Preserving intact habitats not only protects the raptors themselves but everything down the food chain dependent on their regulating influence.

The aerobatic hunters soaring overhead stand as indicators to remind us that seemingly petite predators wield power over far larger systems below.

Accipitriformes in Nepal

Nepal's diverse landscapes--from the Himalayan peaks to the Terai grasslands--host an impressive array of Accipitriformes. Over 30 species reside or migrate through the country, including lammergeiers, Egyptian vultures, crested serpent eagles, and the impressive Himalayan griffon.

The mountainous regions provide important habitat for upland species like the golden eagle and cinereous vulture. Their ability to soar at high elevations suits them to scan vast snowy ridges for signs of movement. The lower foothills and Churia range support short-toed snake eagles and shikras adept at hunting reptiles and small mammals amongst the forests and fields.

The lowland Terai grasslands serve as wintering grounds for migratory steppe eagles, Pallas's fish eagles, and Eastern marsh harriers. Their presence regulates rodent and small bird numbers and contributes to the biodiversity of the Nepalese plains.

While many Himalayan species remain abundant, the degradation of lowland habitats poses long-term threats to Nepal's raptors. Groups like the Nepalese Raptor Research Centre promote initiatives monitoring endangered vultures and reintroducing captive-bred birds into protected habitats to aid conservation.

Culturally, various raptors like the impressive Himalayan griffons feature prominently in Buddhist and Hindu iconography and legends across Nepal. They are also used in falconry and admired for their strength, precision hunting skills, and symbolism of divinity among certain gods like Vishnu.

Given proper stewardship, Nepal's Accipitriformes will continue demonstrating aerial mastery across the country and retain their special significance for generations to come.

Conservation Challenges and Efforts

While many raptor species remain abundant, the IUCN Red List categorizes over 100 Accipitriformes as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered globally. As apex predators, raptors serve as important barometers for environmental threats facing numerous ecosystems.

Habitat loss represents the primary challenge for most species. Deforestation, urbanization, and agricultural conversion destroy critical nesting sites and hunting grounds. Wetland drainage and river diversion also threaten specialized fish eagles and harriers.

Pollution poses insidious dangers - from lead ammunition poisoning condors to pesticide bioaccumulation impacting falcon fertility. Infrastructure like wind turbines and powerlines take a toll on low-flying migrants like golden eagles. Illegal trapping for falconry and bushmeat trade also impacts Asian vulture populations.

Yet dedicated conservation efforts have scored victories through creative initiatives. Captive breeding and reintroduction programs brought California condors back from the brink in the 1980s. Nest site protection, hunting bans, and toxin regulation allowed bald eagle recoveries across North America. Employing GPS tracking confirms threats for specific populations. Conservation groups collaborate with farmers, corporations, and governments to balance development and preservation priorities.

While much work remains for endangered Accipitriformes, targeted programs enabled dozens of raptor species to downlist conservation status in recent decades. Ongoing monitoring and habitat conservation offer hope that these magnificent fliers will continue their reign as apex avian predators. Their preservation is tied directly to our commitment to protect entire ecosystems under their wings.

Conclusion

As a whole, the impressive diversity and sheer global dominance of Accipitriformes provide a powerful embodiment of avian mastery of the skies. From isolated Pacific islands to barren tundra, ease of flight has allowed raptors to conquer territories across the planet. We cannot help but admire the lethal precision that comes from tens of millions of years spent honing aerial hunting prowess.

Beyond inspiration, raptors offer critical ecosystem services that regulate populations and enhance biodiversity within delicate habitats. As predators perched atop food chains, their presence and prosperity reflect that of entire ecosystems sprawling beneath their wings. Threats to Accipitriformes constitute warning signs of wider issues tied to pollution, climate change, and reckless resource exploitation. Ensuring a future where hawks still rule the skies promises benefits across taxa.

Ongoing tracking studies yield new revelations about the epic migrations and global territories managed by various species. International cooperation facilitates restoration efforts for increasingly endangered vultures, eagles, and regional endemics. Advances in genetics, paleontology, and aerodynamic research continue unraveling the evolutionary secrets behind the mastery of these consummate avian predators.

While much progress lies ahead, the success of recent raptor recoveries provides real optimism that committed conservation and passionate study can preserve both aerial titans like harpy eagles and more unassuming masters like the hummingbird-sized black-thighed falconet. For all who admire power, precision, and grace on the wing, we must ensure the skies still belong to birds of prey.